Last year, at the end of November, in all probability on a

Wednesday, my big brother Jeffrey took his own life. Jeff was my best friend

and one of two people there for me every day of my life. The void left by his death is immense.

I have not told many people about it, and it has taken me

months to write this because I could never get past this point. My fingers

hover over the keyboard and right now, this moment, it’s not clear whether I’m

about to get past this point. This is where I've been for months, stuck right here. What to say? How to say it? How to go on?

Jeff was at the top of my cosmology. Almost everything I’ve

experienced or understood in life came to me through the lens of our

relationship, the little brother’s view up. Technically we were half-brothers,

hence the name, but it was never that way, at least not after I was 1, when he

fed me a marble. The story as it came to me was that my dad picked his blue

baby up by the feet and shook the marble free. Thus having failed to rid

himself of the interloper, Jeff decided to be a big brother instead, a role at

which he excelled.

Among many other things, he saw to it that no one would pick

on or beat up the scrawny kid. No one except him. The square red carpet in the living room became a boxing ring,

and no matter who was Ali, Foreman or Frazier, he always won convincingly, and

always in 15 rounds, even if I had been crumpling to the mat since round 3. But

Jeff also took awkward little brother into Philly for soft pretzels and

pinball and ballgames. We shared a room and bunkbeds, and regularly traded spots – whenever

he wanted to switch really, though he was benevolent enough to put together

complicated packages of baseball cards and candy as payment. He was a superb deal-maker and that never changed.

Jeff was good at everything and I was good at nothing,

except school, which he was also good at. Jeff was a lefty pitcher at Lower

Merion H.S. and could throw a curveball. He was a great basketball player

despite being 5'9". He took me to Sam Goody to buy my first album (Styx The

Grand Illusion); the year before that he

took me to my first concert: Kansas, at the Spectrum, 1976. As I was getting

ready he said, “You’re wearing THAT?” It was a stripey T-shirt like what I’d

wear to school. “No, you haveta wear a concert shirt to a concert.” Which is a

problem when you’re 9 and have never been to a rock concert before. The Yes

shirt he loaned me came down to my knees.

I often told him that he was responsible for me

having a life in music. He replied that any big brother anywhere gets their

younger brothers and sisters into music. But the fact is that when I was 12 and

still listening to the lame ’70s, he brought home Joe Jackson records, and Elvis

Costello, and the Pretenders, and a year later, when I visited him in Ann

Arbor, it was suddenly Joy Division and New Order, the Cure and Public Image and the Psychedelic

Furs and a monster-size Plasmatics poster with a giant Wendy O. Williams

mohawked head and the imperative “DON’T BE A WANKER – DON’T MISS THIS SHOW”

Heady shit for a 13-year-old.

Jeff had charisma. That is an understatement. He always had

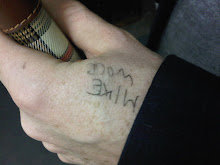

cool friends and girlfriends. Everyone got nicknames: Maven. Golden Boy.

Swampy. He gave me the only nickname that ever stuck, and all of his friends

still use it: Hikey. When I was 5 Jeff and the other big kids deemed me too

small (also: uncoordinated) to play football in the street with them. I went

crying to Mom, who demanded my inclusion. So they let me hike the ball for both

teams and then immediately run out of the way.

There is one story that Jeff took great joy in telling,

especially when he would get to meet a girl I was dating. I was 6 or 7. He was

babysitting me and my sister Julie and somehow, it ended up we were having

cereal, and I made a joke at his expense and laughed. “Stop laughing or I’ll

dump that bowl of cereal over your head!” I can remember just how far over the

line that seemed to my kid mind. No way he’d do it. So I dared him. And he

didn’t hesitate. In finishing the story, Jeff would always lean forward for

emphasis, laughing and talking at the same time, animatedly dragging his

fingers over his face. “Mike was crying and had milk and tears and Frosted

Flakes running down his face!” And so I did. Now I’ll have to tell that story

to anyone new.

Jeff went everywhere and did whatever he wanted, and took me

along a lot of the time. He graduated from Michigan and moved to Minneapolis to

wear a suit for some company. I moved to Minneapolis for college and to be near

him, but by the time I got there less than a year later, he’d already had

enough of that kind of life, the suit, the cold. I helped him move to Southern

California, where he spent the rest of his life. He got a business degree at

UCI and then took a plunge and went for yet another degree, in the “horse

race-track industry program” at Arizona, the only school with such a thing. He was

well-known and well-liked in his field. I kind of hate horse-racing and have

never gone to a track without him, but it was never an issue for us.

Jeff was very good at gambling and handicapping. He always

had a tight grasp on how much he was up or down in any calendar year, and never

got into trouble with money. He bet on horses and played poker — even took home

money at a handful of World Series of Poker events, though to hear him tell it,

all he did was lose. Once I picked up the phone and heard his voice, ashen.

“Hike…I just lost 20 grand at Hollywood.” You WHAT?? And this will explain how he saw the world: He had

expertly handicapped that day’s Pick 6, and the first five dominoes tumbled as

predicted. So did the sixth, but he could not foresee the steward’s inquiry

that DQ’ed his last horse. That money he lost was merely supposed to be his. Another time he did hit the Pick 6 at Hollywood, and I think once more

elsewhere. Like everyone in horse racing, he desperately wished for a Triple

Crown winner to come along and inject some life into the sport. I was with him

at Belmont in 2004 to watch Smarty Jones (the Philly horse!), who was heavily

favored to bring home that third win. We had good seats — Jeff always had good

seats — and we were perched above the finish line. Looking at the heavy odds on

Smarty Jones earlier in the day, Jeff decided the only way to win anything

substantial would be if he composed a typically impossible

trifecta-box-something-something bet. He told me I could go in on his

impenetrable bet if I wanted. I gave him $20.

If you’ve never been to a big horse race, no matter what you

think of the sport, it’s pretty damn dramatic when they come around the home

stretch, and this was the biggest race of the year, maybe decade, and Smarty

Jones had it. One hundred twenty thousand people rose to their feet as one.

And then, for the only time in his career, Smarty Jones got passed in a race.

At the wire. By a 36-1 longshot with late speed. One hundred twenty thousand people, stunned in unison. Even I felt bad for horse-racing. Jeff gave me a sideways

look, grabbed my arm and pulled me toward the betting windows. This was when I

learned that Jeff was a master hedger. Sure he wanted Smarty Jones to win like

everyone else. But he bet against him. And because he was good, he had liked

that 36-1 horse, Birdstone. And my $20 investment got me about $800.

Jeff went to Super Bowls, the Sugar Bowl, BCS championship

games, the Final Four several times, every regional and sub-regional NCAA hoops

weekend in California that he wanted. He went to see the LA Kings win the

Stanley Cup last summer, because he just could. He went to Thailand and all

over Europe. Even if he was never really rich he was a master of anything that

involved money. He knew how to parlay airline miles into free nights at

five-star hotels where you could make it 67 degrees instead of 68. He knew how

to sweet-talk any hotel employee in the world into getting him the quantity and

quality of pillows he needed, and anyone he couldn’t sweet-talk he just bribed.

Jeff took me to the Rose Bowl, where Michigan lost to

Arizona State. He took me to countless Michigan football games in Ann Arbor,

where I saw them lose to UCLA, Iowa and Ohio State. He took me to Amsterdam and

Paris. He flew me out to visit him regularly, and once put me in first class,

“just so you can see what it’s like.” He took me to game 3 of the 2000-01 NBA

Championship and to two World Series, one of them won by our hometown team. That

year we sat in deluxe, heated VIP boxes with free food because the woman who

distributed VIP tickets at Taco Bell – the No. 1 ad-buying client of Fox Sports

– absolutely adored him. Everyone adored him. I adored him and idolized him and would have done

anything to stop the slide he had been on for the past six years.

He wanted to stop it too, and he tried. The vortex of

anxiety, depression and loneliness that consumed him had been building since

2006, when a mystery ailment that was never properly diagnosed put him in the

hospital and left him changed. He knew whatever was wrong with him began then.

So, his suicide was not a sudden thing. It sounds completely insane, but the

possibility of him doing it was a part of our life for years. He talked about

it all the time, to us at least – his closest friends, his ex-wife, me, my mom

to an extent. He didn’t see any reason to live past 50. He had no kids and truly believed that the only things waiting for him were increasing pain and

decrepitude. He didn’t want to be old. We’d see an elderly person walking in

the street, bent and using a cane, and he’d say, “There you go Hike, keep

eating your vegetables and you could have that too.” But he had known happiness

and tried so hard to win it back. He went through a lengthy series of

medications; he wore out therapists. He scouted for other places he might live.

He endured several sessions of shock therapy to try and reset his brain. During

the last one his heart stopped for 15 seconds, and after they successfully

brought him back he felt cheated of an easy out.

Essentially, for the last three years of his life, he tried

to prepare us for this. He didn’t want to hurt us. I think the thought of that

kept him around. He took his time and one by one tried to make each of us understand his decision. The conversations we had…it had been a long time since I

suggested any new option for him. I said I’d move to California to be with him

but he knew I’d be unhappy living there (he was right, but I told him I didn’t

care). The last year, all I tried to do every day was say anything to calm him

down and help him relax. I’ve never had such dark conversations with anyone. He

let me see everything he was feeling, and I’ve never been so sad for anyone

else’s pain. This, my favorite person in the world. I couldn't bear the thought of him leaving, nor could

I bear to see him suffer like he was.

He would be going nuts over Michigan’s run in the NCAAs.

He’d be saying how they had no chance tonight while at the same time checking

out how many miles he’d need to get a first-class ticket to Atlanta. He’d get

there without a ticket and would scalp his way in and would probably make a few

hundred dollars in the process. If he knew I was thinking of posting this today

he’d say, “Wait a day or you’ll mush it for them.”

The last I heard from him was the Monday in November. He

replied to a phone message with a text: “At Clippers game. Had a calm day. I

feel okay.” That was the pinnacle for him, to be out among people

and just be able to be calm.

We scattered his ashes at the finish line — “where it always

went wrong for Jeff,” as his friend Tom said — at Del Mar, his favorite

racetrack. I found the ticket stub from that Clippers game among piles of

others from championships and Springsteen concerts. Next to the PRICE it reads:

$VIP.

I miss him more than words can say.